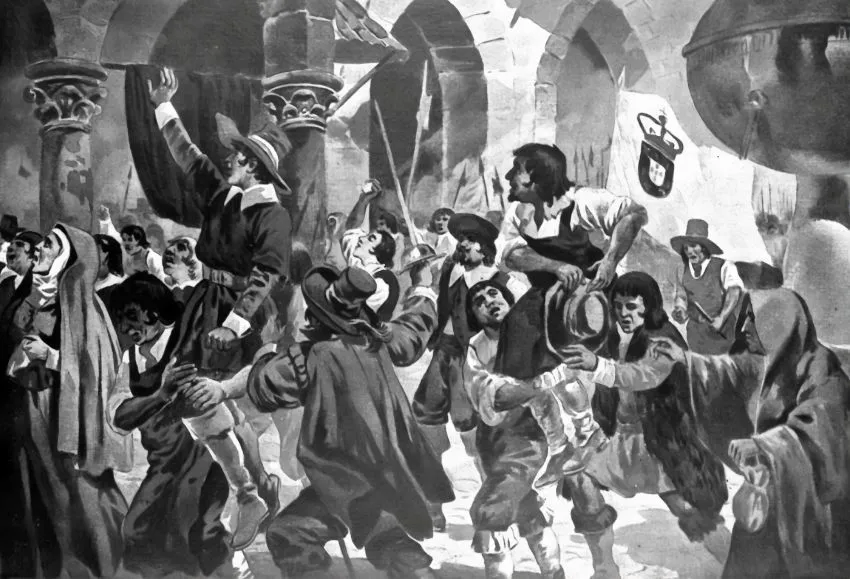

The coup of December 1, 1640, ended sixty years of Spanish rule. It began with farce and violence: Miguel de Vasconcelos, the hated Secretary of State, was killed in a closet and thrown out the window. This was a conservative aristocratic coup, not a popular revolution, that restored Portuguese independence.

There is an almost pathetic moment in the coup of December 1, 1640. Miguel de Vasconcelos, Secretary of State, the man who for years had collected exorbitant taxes on behalf of Madrid, hears the conspirators enter the Ribeira Palace and hides in a wardrobe. The forty Portuguese nobles quickly find him. They shoot him right there, still in the wardrobe, and then throw the corpse out the window into the Terreiro do Paço, where the furious crowd mutilates it. The body remained exposed until the following day.. It is with this combination of farce and violence that Portugal regains its independence after sixty years under the rule of the Spanish "Philips".

This was not a popular revolution in the style of those that would come centuries later. It was a conservative aristocratic coup, planeado por fidalgos que queriam recuperar privilégios perdidos, liderado por um duque hesitante que só aceitou a coroa porque a mulher o empurrou. Mas funcionou. E isso, contra todas as probabilidades, mudou a história ibérica de forma irreversível.

Sixty years of broken promises.

It all begins in 1578, when King Sebastian disappears on the sands of Alcácer Quibir without leaving an heir. What follows is a succession crisis that Philip II of Spain resolves with troops. On August 25, 1580, In the Battle of Alcântara, the Duke of Alba massacred the forces of the Prior of Crato—an improvised army of peasants and freed slaves against Spanish veterans. Portugal lost its independence not because it wanted to lose it, but because the monarchy self-destructed and the Spanish alternative arrived with 20,000 soldiers.

The Cortes of Tomar in 1581 attempted to soften the blow. Philip II, now also Philip I of Portugal, promised twenty-five chapters of guarantees: Portugal would remain legally separate from Spain, only Portuguese would hold administrative positions, the Cortes would always meet on Portuguese soil, and colonial trade would be exclusively Portuguese. It is a “dual monarchy aeque principaliter”"Two crowns on the same head, but two distinct kingdoms.". It looked civilized on paper.

The problem is that paper can hold anything. Philip I still reasonably fulfills his promises during his reign. He lives in Portugal between 1581 and 1583, and creates the Council of Portugal in Madrid. But Philip II (Philip III of Spain) never visited Portugal during his entire reign. (1598–1621), and the Portuguese begin to be treated as inhabitants of a peripheral province. With Philip III (Philip IV of Spain) from 1621 onwards, the promises of Tomar become a dead letter. Portugal officially becomes what it had long been in practice: a source of revenue to finance Castilian wars.

Olivares and the art of destroying an empire.

Gaspar de Guzmán, the Count-Duke of Olivares, became Prime Minister to Philip IV in 1621 with clear ideas:“Muita regna, sed una lex”"— many kingdoms, but one law. In a secret memorandum of 1624, he writes to the king that he must “reduce those kingdoms of which Spain is composed to the style and laws of Castile, without any difference.” There is no subtlety here. It is pure centralism, and Portugal is on the list of targets.".

In 1626 he launched the Arms Union, ...requiring all territories to contribute troops proportionally: Portugal was to provide 16,000 soldiers out of a total of 140,000. This was followed by taxes: the meia-anata (half the annual salary of civil servants), the state monopoly on salt, the water tax generalized throughout the kingdom, and increased excise taxes to 25%. All this allegedly to "defend Brazil from the Dutch," but the money went to wars in Flanders, Catalonia, and against France.

However, the Portuguese empire crumbles. The Dutch captured Salvador da Bahia in 1624., Pernambuco in 1630, Elmina in 1637, Angola in 1641, Malacca in 1641. The Portuguese commercial network—the one that for a century dominated the Indian Ocean and the South Atlantic—was being torn apart while Madrid demanded more taxes and more Portuguese soldiers to fight in Flanders. There is a perverse logic to this: the Iberian Union made Spain's enemies Portugal's enemies, but did not give Portugal the means to defend itself.

| Kingdom / Territory | Soldier Quota |

|---|---|

| Crown of Castile and the Indies | 44.000 |

| Kingdom of Portugal | 16.000 |

| Principality of Catalonia | 16.000 |

| Kingdom of Naples | 16.000 |

| Spanish Netherlands (Flanders) | 12.000 |

| Kingdom of Aragon | 10.000 |

| Duchy of Milan | 8.000 |

| Kingdom of Valencia | 6.000 |

| Kingdom of Sicily | 6.000 |

| Mediterranean and Atlantic Islands | 6.000 |

| TOTAL: | 140.000 |

The revolt that began with a madman named Manuelinho.

On August 21, 1637, Évora is in turmoil. The price of wheat has tripled in three years, there is famine, and there are new taxes. The crowd storms the magistrate's house, burns everything in the square, attacks the councilors' houses, destroys the slaughterhouse scales, invades the prison, and frees all the prisoners. The orders are signed "Manuelinho"—the name of a known local madman, a strategy to protect the true organizers. The revolt spreads to Portel, Faro, Tavira, Setúbal, and Porto. It lasts seven months..

Castilian troops suppressed it in March 1638. But something changed. The Portuguese nobility realized there was a popular will to resist. The discontent wasn't just from nobles resentful of their loss of influence—there was genuine anger in the streets. And in 1640, when Catalonia revolted in the “Body of Blood”"(June 7), killing the Spanish viceroy, Madrid is desperate. It demands more taxes, more troops, and personal service from the Portuguese nobles to suppress the Catalans.". It's the extra request.. In October 1640, the conspiracy was ripe for the taking.

The main characters: a duke who didn't want to be king.

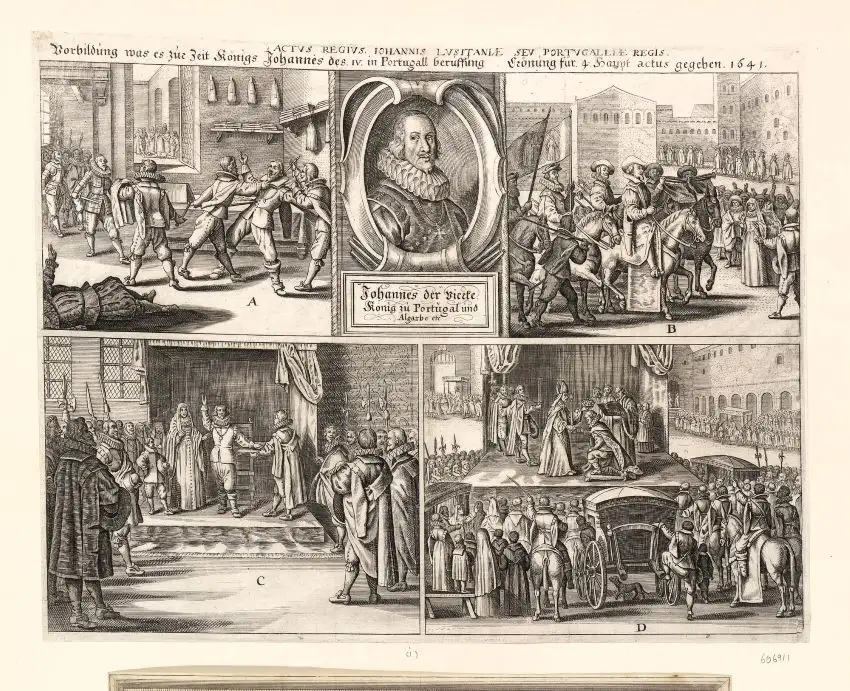

D. João, the eighth Duke of Braganza, has everything to lead a revolution, except ambition. He is the richest nobleman in Portugal, a direct descendant of D. Manuel I through his grandmother D. Catarina. The dynastic legitimacy exists. But João hesitates, delays, refuses to commit himself. He is "a modest man without particular ambitions for the crown." However, his wife "pushes him.".

D. Luisa de Gusmão — and here is one of the most delightful historical ironies — she is Spanish. Eldest daughter of the Duke of Medina Sidonia, one of the most powerful houses in Spain. She marries John in 1633. But when the time comes, she is the one who has the determination that her husband lacks. Legend attributes to her the phrase: "I would rather be queen for a day than duchess for life." It may be apocryphal, but it captures the essence. Without Luisa, there probably wouldn't be a December 1st.

On the other side, there is Miguel de Vasconcelos, the bureaucrat who collects unpopular taxes and concentrates all Portuguese hatred. And the Duchess of Mantua, viceroy, granddaughter of Philip II, chosen precisely because she is a woman—easier to control, Olivares thought. Both will be swept away in hours.

The intellectual architecture of the coup stems from John Pinto Ribeiro, a lawyer trained in Coimbra, administrator of the Braganza family's businesses in Lisbon. He is the one who weaves the network of conspirators, known as the Forty Conspirators. They meet at the Almeida Palace in Rossio. On October 12, 1640, They decide to proceed. On November 30th, John IV confirms the date: December 1st, at nine in the morning.

Anatomy of a coup: from 9:15 am to surrender

On the morning of December 1st, the Forty left the Almeida Palace and crossed the streets of Baixa. They entered the Ribeira Palace at 9:15 am, "thirsty for blood" according to contemporary accounts. The target was clear: Vasconcelos. He tried to hide in a cupboard—the pathetic moment I mentioned at the beginning. They discovered him by the rustling of the papers, shot him while he was still inside the cupboard, then threw the corpse out the window. Down below, the enraged crowd mutilated the body, which remained exposed until the following day.

The Duchess of Mantua is surrounded in her chambers and imprisoned by Antão Vaz de Almada. She offers no resistance—she has no way to resist. The Castle of São Jorge surrenders on December 2nd without a fight.. Within a few hours, the coup is complete.

On the afternoon of January 1st, John was acclaimed King John IV of Portugal in Terreiro do Paço. The Archbishop of Lisbon, Rodrigo da Cunha, organized a thanksgiving ceremony at the Cathedral. During the procession, it is said that the right arm of a crucifix came loose—interpreted as a divine sign. It may have been propaganda, but it worked. On December 6th, John enters Lisbon and is received with jubilation. On December 15th he is formally enthroned. The restoration is complete. Portugal once again has a Portuguese king.

A twenty-eight-year war without decisive battles.

The Restoration War (1640–1668) is strange: it lasts almost three decades, but has only five major pitched battles. The rest are "raids"—cavalry raids, burned fields, stolen livestock. Portugal adopts a fundamentally defensive strategy: it doesn't need to conquer, only to resist. This is a crucial difference.

Spain faces the problem that all great powers in decline face: too many fronts. The Thirty Years' War (until 1648), the war with France (until 1659), the Catalan revolt (until 1652), the war in the Netherlands. When Madrid tries to concentrate forces in Portugal, there is always another crisis demanding attention. In 1643, In the Battle of Rocroi, France crushed the Spanish army, ending Spanish dominance on the European battlefields. In 1647, Philip IV declared bankruptcy. These were not conditions for reconquering Portugal.

Montijo (May 26, 1644) This is the first significant Portuguese victory. Matias de Albuquerque, a veteran of the wars against the Dutch in Brazil, defeats the Spanish with 6,000 infantry and 1,100 cavalry. It proves that Portugal can defend itself. But the truly decisive battle comes later.

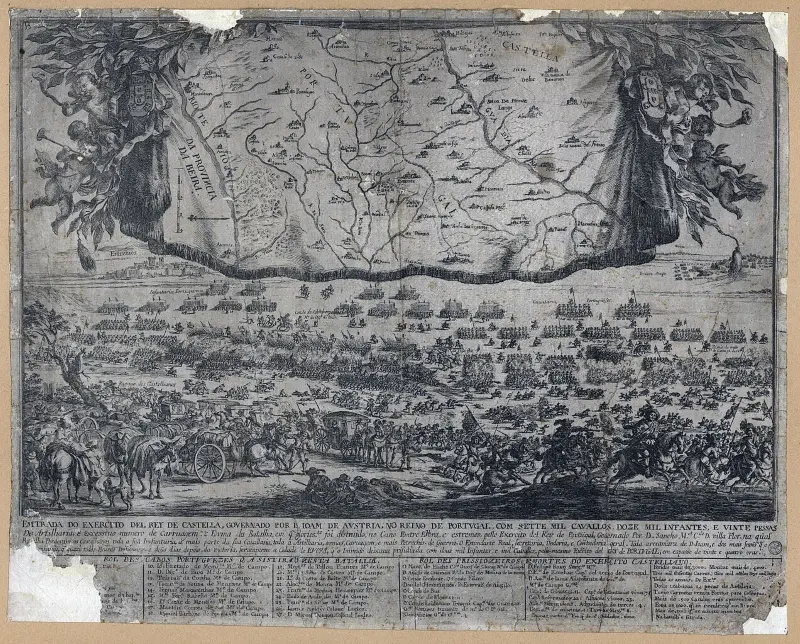

Lines of Elvas (January 14, 1659)The Spanish besiege Elvas with 19,000 men under the command of Luis de Haro. They intend to march on Lisbon. António Luís de Meneses brings a relief army of only 11,000 men, attacks the siege lines and breaks them. Of the 19,000 Spaniards, only 5,300 escape to Badajoz. It is a Spanish humiliation. Meneses earns the title of Marquis of Marialva.

Ameixial (June 8, 1663)John of Austria, illegitimate son of Philip IV, commands 20,000 men who capture Évora. The Portuguese, under Sancho Manuel de Vilhena and the German mercenary Schomberg, counter-attack with 17,000. A crushing Portuguese victory. They capture all the Spanish artillery. John of Austria retreats to Badajoz, his military career over. This battle convinces London and Paris that Portugal can win.

Montes Claros (June 17, 1665)The last Spanish attempt. The Marquis of Caracena brings 23,000 men (many German and Italian mercenaries). Marialva and Schomberg command about 30,000 Portuguese. Nine hours of intense combat. The Spanish lose 4,000 dead, 6,000 prisoners, and 14 artillery pieces. The Portuguese: 700 men. It's the end.. Spain realizes it cannot reconquer Portugal by force of arms.

Diplomacy: marriages, colonies, and betrayals

Portuguese diplomacy after 1640 is an exercise in brutal realism. Portugal needs allies against Spain, but the allies have their own interests. Treaty of Paris (1641) The treaty with France lasted until 1659, when Cardinal Mazarin broke it. In the Treaty of the Pyrenees (1659), France abandoned Portugal and made peace with Madrid, even recognizing Philip IV as the legitimate king of Portugal. It was a diplomatic betrayal that left Lisbon isolated.

England becomes the salvation, but the price is high. Catherine of Braganza, daughter of John IV, marries Charles II in 1661. The Portuguese dowry is colossal: Bombay and Tangier, two million Portuguese crowns (£300,000 — about half the English treasury), full commercial rights in Brazil and the East Indies. England sends 2,000 infantry soldiers and 500 cavalrymen.

Bombay becomes the jewel in the British crown in India. Tangier is evacuated in 1684 under Moorish pressure. The financial debt burdens the Portuguese treasury for fifty years. But the alliance is decisive. The English brigade under Schomberg, many of them veterans of Cromwell's army whom Charles II wanted out of England, is decisive in Ameixial and Montes Claros.

With the Dutch, there was the Treaty of The Hague (1661): Portugal recovered Brazil, but ceded Ceylon and the Moluccas, paying eight million florins in compensation. This formalized the collapse of the Portuguese Asian empire. Malacca fell in 1641, Ceylon was completely conquered in 1658, and the Malabar Coast in 1663. What remained in Asia were bases in Goa, Macau, and Timor—shadows of its former splendor.

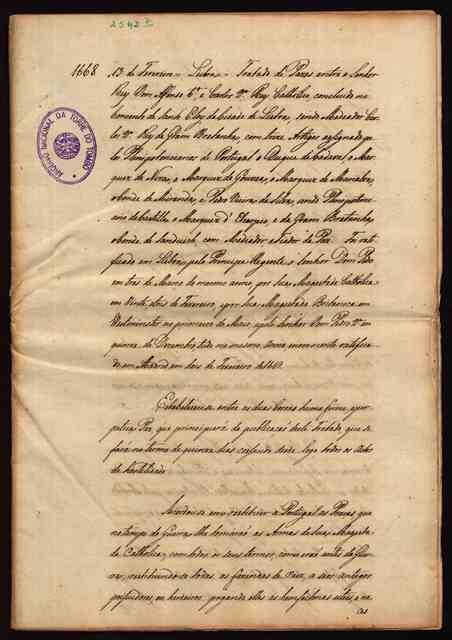

The Treaty of Lisbon and Spanish recognition

On February 13, 1668, Spain finally recognizes Portuguese independence in the Treaty of Lisbon. The mediation is English, carried out by Edward Montagu, Earl of Sandwich. Queen Mariana of Austria, regent for her minor son Charles II, signs on behalf of Spain. Prince Regent Pedro (the future Pedro II), who had ousted his incapacitated brother Afonso VI, signs on behalf of Portugal.

The terms are simple: Spain recognizes the House of Braganza, Portugal retains all colonial possessions. except Ceuta, which never recognized the dynasty. A thirty-year ceasefire was established. Technically, the war was over. But rebuilding Iberian dialogue proved more difficult than signing treaties.

The legacy: an identity forged in resistance.

What remains of 1640? First, the confirmation that sixty years were not enough for Spain to integrate Portugal. The promises of Tomar were broken so systematically that they generated resistance. There is a lesson here about empires and autonomy: paper can hold everything, but real policies create real resentment.

Secondly, Portugal is irreversibly reorienting itself towards the Atlantic. Asia is lost—the Dutch control the Indian Ocean, and the English will soon dominate it as well. But Brazil becomes the economic center of the empire.. From 1645 onwards, the heir to the Portuguese throne used the title of Prince of Brazil. Brazilian sugar, produced with enslaved African labor, replaced the Asian spice trade. Angola became subordinate to Brazil as a source of labor. It was a triangular Atlantic empire: European manufactured goods were traded in Africa for gold and enslaved people, who went to Brazil to produce sugar, which was then returned to Europe.

Third, there is a process of cultural and political “de-Iberianization.” Portugal turns to Western Europe—France and England—in search of ideas and skills. The rejection of Spanish influences that permeated life during the Union becomes almost obsessive. What historians call the Portuguese “political nation” emerges—an identity defined by opposition to Spain.

But there are ambiguities. This was not a “nationalist” revolution in the modern sense. It was a conservative aristocratic revolt. The nobles wanted to recover privileges, not create a bourgeois republic. The people supported it, but did not decide. The Braganza dynasty, which ascended the throne in 1640, would rule until 1910—almost three centuries of monarchical continuity. The Restoration was simultaneously a radical break and a profound preservation of social structures.

And then there is the military question. Historian R.A. Stradling argued that the war with Portugal contributed “more than any other factor to the eventual dissolution of Spanish hegemony.” It’s a strong statement, but it’s debatable: for twenty-eight years, Spain bled resources dry in a war it couldn’t win, distracting itself from greater threats. Extremadura and Galicia were devastated. Each Portuguese victory—and there were many—eroded the reputation of Spanish arms.

A wardrobe and an empire

I return to the initial moment: Miguel de Vasconcelos hidden in the closet, the rustling of papers betraying him. There is something almost Shakespearean about that scene. The representative of sixty years of Spanish rule, the man who levied unpopular taxes and concentrated Portuguese hatred, dies like a cornered rat. Then he is thrown out the window and the crowd dismembers the corpse.

Portugal regained its independence not through a large popular uprising, nor through nationalist idealism—those would come centuries later—but because a resentful aristocracy realized that Spain was too weak to stop them and that there was enough popular anger to support them. It was political calculation, strategic opportunism, and, in the end, enough courage to risk everything on a December morning.

What intrigues me is this: was sixty years too long or too short a time to integrate Portugal? If the Philips had kept their promises at Tomar, if they had treated Portugal as an equal kingdom and not as a peripheral province, We would have a unified Iberia today.Or was Portuguese identity already too strong in 1580 to ever accept dissolution, regardless of how many promises Madrid fulfilled?

There is no right answer. But there are facts: in 1640, it only took one day to undo what sixty years had failed to consolidate. A cupboard, a gunshot, a defenestration. And Portugal was Portugal again.